With thoughts from Jessica McHugh, Holly Lyn Walrath, Donny Winter, Marisca Pichette, and JG Faherty

Definitions

The term “dark poetry” is vague and amorphous—try to pin it down, and it will slip away. Some people may find that frustrating, but writers (like me, like those who shared their thoughts with me), love the freedom of the term. While details of our individual definitions may differ, we agree on the overall concept: dark poetry is, well, dark.

Jessica McHugh, a 2x Bram Stoker Award-nominated poet (The Quiet Ways I Destroy You), says that dark poetry falls into a few categories:

“The explicitly dark, which borders and blends with horror poetry, maintaining a scary or unsettling vibe throughout. The surprisingly dark, which lulls the reader into a false sense of security before pulling out the rug. The emotionally dark, which tackles rough but relatable topics like death, isolation, mental illness, etc. through chilling metaphors and imagery.”

“But,” she says, “they also intersect and borrow conventions from each other. I’ve found gothic poetry can often embody many of these themes and techniques in one piece.”

Holly Lyn Walrath, author of Numinous Stones and publisher at Interstellar Flight Press, breaks her definition into two categories:

“One is horror focused and draws on the tropes of horror, with a goal of creating fear/ick in the reader. The other draws on dark themes, like death, depression/anxiety, trauma, violence, etc.”

Like McHugh, though, she says “Betwixt the two is a lot of overlap.”

Donny Winter (Feats of Alchemy) defines it more as one large subgenre with a lot of sub-subgenres:

“I’ve always defined dark poetry as an over-arching genre possessing messages, themes, and imagery related to what many may consider the darker side of human experience. Some sub-genres may include dystopian, cyberpunk, sci-fi, horror, gothic, nature, and many others.”

Author of Songs in the Key of Death JG Faherty explains that for him, dark poetry “[…] focuses on creating an unsettling mood. The associated emotions might be unease, concern, depression, anxiety, and yes, even fear. Dark poetry can make you think (a science fiction poem about the dangers of AI) or make you weep (a gothic romance poem about someone losing their lover to a tragedy. Or being haunted by their ghost!). Some of my poems in my collection Songs in the Key of Death deal with evil dentists, brain parasites, suicidal thoughts, alien invasions, serial killers, body dysmorphia, and the end of the world. It is the subject matter that is dark in dark poetry, but there doesn’t need to be anything horrific or supernatural about it.”

Conventions

As for qualifications, poet Marisca Pichette (Rivers In Your Skin, Sirens In Your Hair) says they’re pretty simple: “I think the qualifications for dark poetry are very basic: make the reader uncomfortable, lead them into shadow, and craft an image that disturbs in some way. There are the obvious themes of death, trauma, grief, and anger—but dark poetry can really take any form. It can be an empty room, whispering of something that was. It can be a throat raw from shouting, eyes red from crying. It can be a question posed without answer. That’s what I love about dark poetry.”

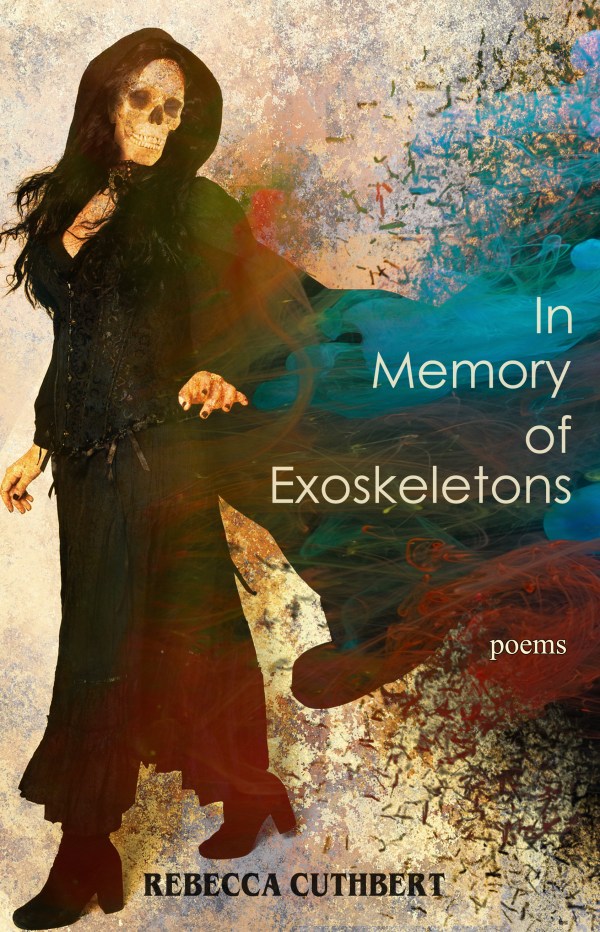

As for myself (Rebecca Cuthbert, In Memory of Exoskeletons), I think the vastness of the subgenre of dark poetry makes it difficult to call out necessary, or even likely conventions. Some of my poems in my first collection are about the topics mentioned: grief, depression, body image issues, trauma. Other topics are the pain that comes with hope, the disappointment a former self may find in a current self, and the unfairness of “No Dog Walking” signs in cemeteries.

Inspiration

As for why I write it, my thoughts align closely with McHugh’s. She says dark poetry is “[…] simply what tumbles out when I’m trying to articulate a certain subject or feeling. That said, I do find the vocabulary of the dark and terrifying provides colors I enjoy painting with most. Evocative, visceral verses. Poetry you can hear and smell, even when you don’t want to. Scenes with teeth that scrape and gnaw the brain long after you’re done reading. It sounds demented, but that’s what sparks artistic joy in me.”

Pichette suffers from the same wonderful condition.

“I can’t seem to write about something without showing the darker nature lurking under the surface,” she says. “Whether real or imagined, you can find horror in just about anything. As for reading dark poetry, I gravitate to it for much the same reasons. Poetry is often confrontational, and I love when a piece sends a shiver through me, or creates that tingling realization that more is being said than I originally thought. Layers are so important in poetry, and darkness is one of the best to explore.”

Winter writes dark poetry because he’s able to share his story, the good parts and difficult parts. “Additionally,” he says, “I think dark poetry is a more powerful vehicle for creating social commentaries about societal atrocities, considering it roots itself in that vulnerability.” And from the other side, “[R]eading dark poetry [is great] because experiencing the vulnerability can be incredibly cathartic, especially if you’ve experienced similar trauma. Other peoples’ healing experiences, including the darker aspects, can act as roadmaps for our own healing.”

Misconceptions

“I think people imagine all dark poetry as Edgar Allan Poe-esque descents into madness and self-loathing, which is obviously not true,” says Pichette. “The best dark poetry grapples with something very real, and doesn’t settle for shock value. In all writing, we’re striving to go deeper, view problems from new angles and imagine other solutions. Rather than simply offering a known horror, the best work spurs some kind of epiphany. What if Poe’s Raven wasn’t a bird, but a manipulative partner, orchestrating the narrator’s downfall? Such a revision can shed light on modern issues and give the reader a different thrill as the truth is revealed.”

Me again (Cuthbert). I’m going to say something here others may very well disagree with: I think dark poetry can be kinda happy, and not just for those aspects like catharsis and connection. Some dark poems are farewell letters, and there’s joy in saying goodbye. Others are funny—in my next hybrid collection (Self-Made Monsters, 2024), I have a feminist horror poem called “Mistress Meg O’Malley,” about a vampire sex worker who definitely eats people, that sort of cracks me up. But, I guess one person’s emotional disturbance is another person’s sick joke.

You don’t have to take our word(s) for any of this, though. If you’re interested in dark poetry, read a bunch of it. If you like it, emulate what you see, then revise it to be something entirely yours.

A few recommendations…

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

“Goblin Market” by Christina Rossetti

“Rainy Night” by Dorothy Parker

“Voices of the Dusk” by Fenton Johnson

“The End of Little Dreams” by Julia August

“History of Orconectes” by Dyani Sabin

“Crow Daughter” by Gabriela Avelino