I’m writing this post because of comments I have seen recently on social media in response to publishers’ “open submissions” announcements. Of course I will not name names–it’s not a burn post. But many of us have had to learn the submissions process the hard way, and I hope this post will help folks avoid the mistakes I’ve seen and the mistakes I’ve made myself. Now I can’t cover every faux pas here, and most publishers will absolutely overlook small mistakes and mixups. (Like, if someone wrote to “Undertaker Press” by mistake rather than “Undertaker Books,” no biggie.) Here are a few things to try to avoid, though, with some tips on what to say or do instead.

- Do not announce yourself like a boxer jogging into the ring.

This imagery comes to you courtesy of Heather Daughrity of Watertower Hill Publishing and Parlor Ghost Press. It’s the perfect analogy for what I have seen on these social media posts and in emails I’ve gotten as an editor.

Some authors, before even mentioning their current project or submission, feel they need to yell through a megaphone, often exaggerating their accomplishments, and generally putting their ego first. Not a good look, I promise you.

The place for information about you is in a short, factual, third-person bio paragraph you would include in a cover letter/email with your submission. Stress on “short.” (And do not put it on social media in a comment on a publisher’s post.) Start that paragraph with a personal note about yourself and follow it up with a few publications/accolades and then where folks can find more information about you (hopefully, your author website).

2. Do not beg, grovel, put yourself/your work down, or share a sob story.

Be friendly, confident, and at least a little bit professional. I have seen statements in the comments section like “I have a book that is like Star Wars meets Anne of Green Gables but you probably wouldn’t want to read it.” Problems: zero confidence makes me think it’s probably not that good, but also, you made up my mind for me, which is kinda rude and presumptuous. So let’s revise that. It would be much better if the person said something like: “I have a novel manuscript ready that could be described as a mashup of Star Wars and Anne of Green Gables. Beta readers have told me it’s a fun read and not like anything else they’ve read. If you’d like to take a look, I’ll send it along.” Of course, only say that if it’s true.

Other cringeworthy comments, which of course I’m paraphrasing/imitating:

“Wow I’m so glad to see this sub call. I haven’t had anything published in over a year because I had to move and then my cat died and I lost my job. I wanted to self-publish but I never really got around to it and I thought I’d never write another thing but hey, I could send something to you!” (TMI, and a weird vibe right away; might also signal to the editor, rightly or wrongly, that you would be difficult to work with and/or clingy.) Instead, how about “This looks like a great submission call and I have something that would fit. I’m excited to send it!”

“Oh cool I love your books! You put out the best books in the industry and I tell everyone you’re the best! Publishing with you would be a dream come true and would be the best thing that ever happened to me!” (Even if that is totally true, it SOUNDS like corny flattery. Compliments are appreciated, but in moderation.) Instead, try “You put out great books and have an impressive reputation. I’m definitely sending you something!”

3. Try not to ask questions in the comments section that could be answered by the publisher’s post itself or by a quick look at their website or social media.

Comments in this category of “Please No” are “What kind of submissions do you want?” (That will be in the post or on the website.) “What books have you published?” (Go to the website.) “Who else has books with you?” (Again, go to the website.)

It is absolutely fine and great to ask questions. Just make sure the questions you are asking can’t be answered by a one-minute review of the post or a quick website search. And, of course, since we all miss things that are right in front of our faces (because I have done this a million times), when you realize your goof, offer a quick apology. “Sorry! That was right in the post. My bad!” Editors and publishers are humans too. But you want them to know you don’t take their time and attention for granted.

4. Do not say rude things.

I cannot count the times I have seen absolute rudeness in response to publishers’ submissions calls: “Why would I even submit to you? You’re a joke.” “My work is worth money. Recognition doesn’t pay my bills!” “You aren’t a professional magazine if you don’t pay writers!”

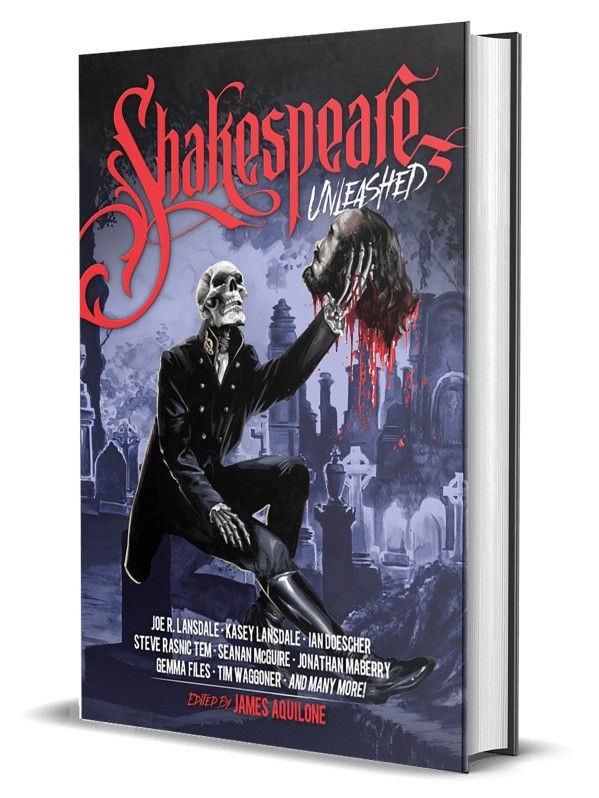

Lordy. This is one of those “Don’t like it? Keep scrolling” situations. It’s true that editors/publishers should announce whether or not it’s a paying publication. But when it does not pay, or when the payment is token, don’t be nasty, and don’t assume every other writer out there has the same publication goals you do. A friend of mine submits work to non-paying calls, because he’s just trying to meet other authors and folks in the industry, and get his name out there. I have submitted to non-paying calls because the publication’s theme is really cool, or I like what they put out, or it’s for a charity I care about , or because I know the editor to be great, or because I know that publisher submits authors’ work for awards like the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Maybe a writer is just starting out, and getting a story or poem in a non-paying publication would mean the world to them. Do what you want to do, submit or don’t, but keep the vitriol to yourself.

“I’d never submit work to you! You’ve published [author I hate/author who has behaved badly]!”

Okay. I know this is a tricky one. But think before you type.

It could be that yes, a publisher has put out a book by someone who acted badly. We’ve seen it all too often in the horror community. But when did they put out the book? Was it BEFORE the author in question was known to be a jerk? Could the contract have been signed before that point? Contracts are legal documents, and before you type an angry comment to this here post lemme ask you: Are you a lawyer? A judge? If not, still those itchy fingers. Some publishers have what is often called a “behavior clause.” This usually means that, should an author behave badly, in any number of ways, the publisher can immediately cease production of their book and the contract is void. But if a publisher does NOT have this clause, they may be stuck with that author and that book, at least for the duration of the contract, which can range from six months to several years.

Here’s something else that a lot of righteously angry people won’t want to hear: People change. PEOPLE CHANGE. They are capable of personal growth, and learning, and repentance, and behavioral correction. It’s possible that a person did or said something terrible a long time ago, and has since become a better person. (This applies to like, non-felonies, of course–I’m not saying you should forgive every murderer and assaulter out there.) There is an expression I love: “When you know better, do better.” I’m not going to hate anyone because of something they said 20 years ago. I’m sure that I myself said horrible things 20 years ago, when I was young and ignorant and sheltered. I’m sorry for all of them, even the ones I don’t remember saying (because alcohol and I were way too close in my 20s). So I will give people the grace that I hope to receive. People. Change.

I’m going to stop there. Happy posting and happy commenting, everyone.